Fighting in the NHL: Should it be Allowed?

December 17, 2014

Some foul words are tossed back and forth, there is a tap on the shins, and the gloves are dropped. This is the scene of one of hockey’s oldest traditions: fighting.

Fighting in ice hockey has been in the sport since its creation. A fight in hockey is usually performed by enforcers, or goons, players whose role it is to fight, and intimidate, on a given team. Fighting is governed by a system of written and unwritten rules. The NHL official written rule declares that “A fight shall be deemed to have occurred when at least one player (or goalkeeper) punches or attempts to punch an opponent repeatedly or when two players wrestle in such a manner as to make it difficult for the Linesmen to intervene and separate the combatants.”

Fighting in ice hockey has been in the sport since its creation. A fight in hockey is usually performed by enforcers, or goons, players whose role it is to fight, and intimidate, on a given team. Fighting is governed by a system of written and unwritten rules. The NHL official written rule declares that “A fight shall be deemed to have occurred when at least one player (or goalkeeper) punches or attempts to punch an opponent repeatedly or when two players wrestle in such a manner as to make it difficult for the Linesmen to intervene and separate the combatants.”

Although fighting is a part of the rules, there are still punishments for it. After a fight, both parties are usually given a major penalty, five minutes in the penalty box. Also if one of the fighters is deemed an instigator or an aggressor, his team will be given an extra minor penalty, two minutes in the penalty box. An instigator is a player who goes out of his way to start a fight, even when the opposing party does not want to, and an aggressor is a player who tries to continue throwing punches on an opponent who is in a defenseless position.

Although fighting has been in the sport since its beginning, there is now talk of taking it out of the game. Some people believe that fighting actual protects players because it leaves players accountable for their actions.

“You have a game that’s very physical, very fast, very emotional, very ‘edgity,’ and it’s played in a confined space,” Garry Bettman, the commissioner of the NHL, said in a recent interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. “Every now and then there needs to be an outlet to keep the temperature from worse things happening [on the ice].”

The players seem to agree with Bettman as Brian Bickell, a player for the Chicago Blackhawks reportedly said, “We’re the only sport where fighting is allowed and you feel like it’s part of the game. The people running the teams want it, players want it, the fans want it, and the bottom line is it prevents players from running around looking to hurt guys and holds them accountable for their actions.”

Scott Stevens, a former NHL tough guy/star and former assistant coach for the New Jersey Devils, says, “I believe fighting has a place in hockey if it’s for the right reasons. I’m all for two guys dropping the gloves for a heat of the moment thing. The game is very physical and intense that’s what makes it so special. I’m totally against staged fights that have no reason, two guys that have no reason other than it’s their so called job.”

Stevens also commented, “If fighting was taken out [of hockey] I believe the game would get dirty and we would possibly have more stick related incidents which would not be good for the game.”

Seth Ferguson, a referee in the Ontario Hockey League, commented, “Fighting also provides an outlet for frustration and emotion that would be taken out in stick work if it was not there. In some lower junior leagues where fighting has almost been removed, there is trash talking and pushing and shoving at every stoppage and more stick work. Trash talking behind a mask when the linesmen are in is not part of the sport.”

When asked what would happen if fighting was taken out of the sport Ferguson added, “Games would get so bogged down by whining, fake toughness, and other nonsense when a fight would solve the issue quickly. It is far better to deal with the problem right away [to fight] rather than have it stew for the rest of the hockey game and lead to other problems down the road. This is a hard thing to explain, but when you’re on the ice, you feel the build-up on tension and stupidity. After a good fight, this all seems to dissipate. However, there are exceptions, like a fight-filled game. But think of the other options [stickwork, cheap shots] that would be used if fighting wasn’t there.”

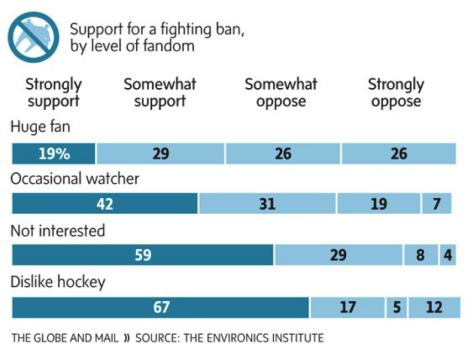

Fighting also happens to be one of the most iconic parts of hockey. Sameer Jhaveri, a senior at the Williston Northampton School, is not a big hockey fan, but when asked what his favorite part about the sport was, he answered, “The first thing that comes to mind is the most exhilarating part of hockey: fighting.”

He later added, “The players have to find a way to entertain the fans. These people come here during their free time to be entertained and they want to see some fights.”

Others believe that fighting is dangerous and barbaric and that it should be taken out of the game.

Dr. Charles H. Tator, a neurosurgeon and researcher at Toronto Western Hospital who directs programs to reduce head and spinal-cord injuries in sports, was interviewed by a writer of The New York Times and he said, “We in science can dot the line between blows to the head, brain degeneration and all of these other issues. It’s time for the leagues to acknowledge this serious issue and take steps to reduce blows to the brain.”

Those steps, he said, include “getting fighting out of the game.”

People believe that fighting can have both a physical and a mental toll on enforcers.

Derek Boogaard played six seasons in the NHL with the Minnesota Wild and the New York Rangers, totaling 589 penalty minutes. While Boogaard played in the NHL he was one of the most feared enforcers at 6 feet 8 inches and 260 pound, he was constantly giving and receiving blows to the head. On May 13, 2011, Boogaard was found dead. His death was ruled to have been an overdose on painkillers and alcohol.

In an article, Jeff Klein, a writer for The New York Times, wrote, “After Boogaard’s death his brain was examined by researchers at Boston University. The researchers looked for C.T.E. (Chronic traumatic encephalopathy) which manifests itself in symptoms like memory loss, impulsiveness, mood swings and addiction. They said they found striking evidence of the disease in Boogaard’s brain.”

Klein also commented, “In Boogaard’s case, the Boston University researchers said it was impossible to know whether the condition was caused by blows he sustained in fights.”

Dr. Robert Cantu, a co-director of the Boston group and a prominent neurosurgeon in the area of head trauma in sports, said the evidence was strong enough to say that league officials “are putting people at risk by allowing fighting.”

Mike Chamber of The Denver Post wrote in an article, “The mere act of allowing fights is also why many sports fans view hockey as a niche sport, one that will never become mainstream because of its sometimes barbaric nature.”

In the past, coaches have also bullied players into fighting. Mike Chamber interviewed Scott Parker, a former Colorado Avalanche enforcer, who at 35 is dealing with symptoms affiliated with head trauma symptoms. Parker had some harsh words about his former coach, Bob Hartley. “He was a junior B goalie trying to tell me how to fight. He was always just degrading me. Not to be a [wimp], but he was a bully,” Parker said. “And he could be because he was in a position of authority. What was I supposed to do as a rookie? Go tell him ‘[expletive] you’? I did that stuff at the end of my career, but at the beginning of my career I was just a chess piece to him.”

Parker also estimated that he suffered around 25 concussions, and said there were several times when he was so banged up he told Hartley he needed a night off, or at least a game off from being asked to fight.

“He would call me a [expletive], say that Hershey [the Avalanches’ former minor-league affiliate] would be my next stop, where I’d be ‘smelling chocolate fumes all day long.’ I remember I thought I had a broken foot and told him about it, and he called me a [expletive] and said Hershey would love me,” Parker said. “Nobody needed to question my commitment to doing my job. But I was just constantly belittled by Bob Hartley. I really have no respect for the man.”

The pressure Parker talked about might not be as prevalent in today’s NHL, as fewer teams have a self-described “enforcer,” but it still exists.

“If you’re hurt, it doesn’t matter. You’re made to think ‘I have to fight, or I’ll lose my job,’” Parker said to Chamber.

Dr. Michael Cusimano, a neurosurgeon at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto who is involved in efforts to reduce sports injuries, talked to Chamber, and criticized the NHL for saying they needed more data on fighting.

“We heard this about 40 years ago with cigarette smokin g,” Cusimano said. “Sure, there can be more evidence, but there’s some evidence out there that fighting is clearly a cause of brain injuries.

g,” Cusimano said. “Sure, there can be more evidence, but there’s some evidence out there that fighting is clearly a cause of brain injuries.

Although fighting may not be taken out of the game completely, the NHL continues to add more rules in an attempt to minimize fighting and protect the players. Beginning this season, a minor penalty is assessed to a player who takes off his helmet in order to fight. Also, new players or those with 25 or fewer games in the league must now wear a visor, with veterans being grandfathered in and having a choice to wear a visor or not.

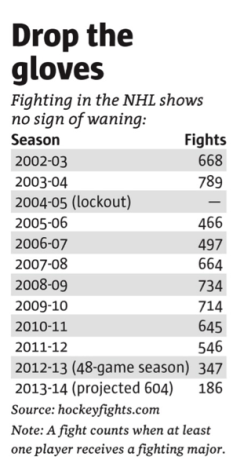

Is fighting going to be eliminated from the game in the near future? Ferguson says, “Fighting is definitely being phased out of the game, at least at the major junior level. Now there are suspensions for having over 10 fights per season. It would not be surprised if in the next five years there is a game misconduct assessed for fighting. I disagree with this and feel that fighting has been a part of the game since its creation. In such an emotionally-filled and physical setting, fighting is bound to happen.”

Stevens also responded to the same question, saying, “I don’t feel fighting will come to an end but it just will happen less just like it is in today’s game. If and when it happens it should be spontaneous, not staged.”

“The fighter that plays three or four minutes a game is over,” said Brandon Bollig, a player for the Chicago Blackhawks, who has actively been trying to expand his game to become more than just a fighter. “You definitely have to be able to get around the ice. The game is obviously changing, that’s no secret. But there’s still a place in the game for fighting.”

In a sports industry that is forever saying, nobody can say who’s wrong and who’s right about this topic. The real question is which argument will win the fight?