Where we sit in class is a mix of friendship dynamics and seating preferences. But another huge, often unconscious, role is gender, race, international status, and other identities.

Williston classes are getting into a rhythm, as are our seating arrangements; people have claimed their spots and the people they will sit next to. They are probably sitting next to friends, and their friends probably look like them. Girls hanging out with girls and guys with guys is not a foreign concept.

Ava Howard, a senior day student, experienced a common scenario of gender solidarity within a class this year.

“I have pre-calc, there are only three other girls in that class,” she said. “We locked eyes from the other side of the room, and it was a sigh of relief, like ‘We are not going to be alone.’ And so, we sit together.”

Nasheen Gibbs, a senior boarder, saw a gender divide while getting ready for Athletic Performance (AP).

“Just the other day I was sitting in the gym, waiting for AP to start, and literally it was cut in half with one side of the gym being the girls getting ready and the other side being the guys,” Nasheen noted. “It’s an athletic space so girls would rather stick with girls.”

River H., a sophomore boarder, has a class with a strict gender divide.

“We were perfectly split; boys on one side and girls on the other,” River said. “And I remember the teacher bringing it up and saying, ‘Oh we’re perfectly split.’ Which I thought was kind of interesting. So, there is for sure that gender divide, very clumped up even when they are not friends.”

But let’s take a step back and think about the first thoughts people have when choosing their seats to see how these divides could happen. This could be looking at gender, which is something River does to make sure he isn’t making anyone feel uncomfortable.

“If I don’t know anyone in the class I will sit next to the boys because I don’t want anyone feeling creeped out,” he said.

Wakanda Hu, a junior international boarder, looks for girls for someone she can talk to and have a shared experience with.

“I don’t know, I just feel like I will be more likely to talk to girls than boys,” she said. “I have more similarities with them [girls] and people tend to get closer to people that are the same.”

Ava notes how race is also a factor when looking for someone to sit with, especially in history, where discussions about race occur and racial support is more needed.

“There is also a racial thing I do in my head, whether it’s intentional or not, where almost every year I’ll have a Black student in my class and if I know them, we’re like ‘ok,'” she said. Ava finds this occur “in history, especially [because] we know in history we are going to be brought up and it’s a uniting thing.”

A 2007 research paper, “Why the Black Kids Sit Together at The Stairs: The Role of Identity-Affirming Counter-Spaces in a Predominantly White High School,” supports Ava’s sentiment.

“Black adolescents are not only encountering racism and reflecting on their identity, but their White peers, even when they are not the perpetrators of racism, are also unprepared to respond in supportive ways,” it reads. “Thus, Black students turn to one another for the much-needed support that they are seeking.”

A senior boy who chose to stay anonymous notes that international kids also tend to stick together.

“They will surround themselves with people with similar opinions and people of similar origins,” he said. “Like groups of international students from similar areas will group together.”

For international students, a system of support is often needed. They are in a new country, often speaking a new language, and are consumed by a new culture.

When asked why people sit with people of like identities, there was a consistent mention of comfort by the students and teachers interviewed.

Comfort and gender solidarity go hand in hand. Nasheen believes that gender solidarity is needed in things like athletic spaces but also in the classroom.

A 2014 research paper “Gender-Based Relationship Efficacy: Children’s Self-Perception in Intergroup Contexts” mentions the reason children do not interact with other-gender peers is due to not being comfortable.

“It appears that children feel a lack of comfort with and exaggerated sense of ‘otherness’ about other-gender peers,” the paper explains.

That research paper, in combination with a 1995 paper titled “Gender Segregation among Children: Understanding the ‘Cootie Phenomenon,’” points to divisions starting as children who are socialized into believing there are harsh differences between girls and guys when that’s not necessarily true.

The 1995 paper argues that the differences between the genders are small, if at all.

“Boys and girls are not nearly as different from each other as most people believe them to be.” Later it gives the example, “Even when sex differences are found, they usually represent highly overlapping distributions. Take visual-spatial skills, for example: although some studies find that boys do better in this domain than girls, the overall difference is small; furthermore, many girls do better than the average boy, and many boys do worse than the average girl.”

People are sitting next to people they feel comfortable with, and not necessarily with people of similar interests or abilities, which is often not tied to identity.

Justin Brooks, a history teacher, understands international students sticking together because he too was a newcomer to academic spaces in England and Australia.

“They are newcomers to a culture,” he said. “I have been an international student four times, [and] every single time I flocked to the other international students because we were all newcomers.”

These international groupings can help each other translate, understand the subject matter, and provide a space free from American culture.

Beatrice Cody, a Latin teacher, posits that students first arrange themselves based on identity because of the challenges the classroom provides.

“People are creatures of habit, so they start out that way because it’s scary to go into an unfamiliar situation. Classrooms can be scary because you have to showcase your abilities,” she said.

Being vulnerable is a challenge, but it is a little less challenging if we are around people that will support us. We flock to our friends in classes for this reason. Yet, we do make friends with people who do not have the same identity as us. However, when mixed-gender friendships are viewed from an outside lens, they can be made uncomfortable, despite the members of the friendship being comfortable.

Ava is frustrated at the heteronormative lens some of her closest friendships, which happen to be with boys, are viewed through. Heteronormative is the assumption that everyone is straight, and often that girl-boy relationships are romantic.

“I think that there is that social aspect where when you see a girl with a guy you don’t always perceive it as friends, and so when you’re seen walking around with a guy, people unconsciously absorb it in a romantic context,” Ava said.

Cody sees a lot of mixed friend groups, but notices that if they were to sit next to each other in class they could “probably [be] perceived as being romantically interested in each other.”

These dynamics put girl–boy pairings in an interesting spot. They are under a lot of scrutiny that same-gender pairings are not. This could very much deter such pairings from presenting in class.

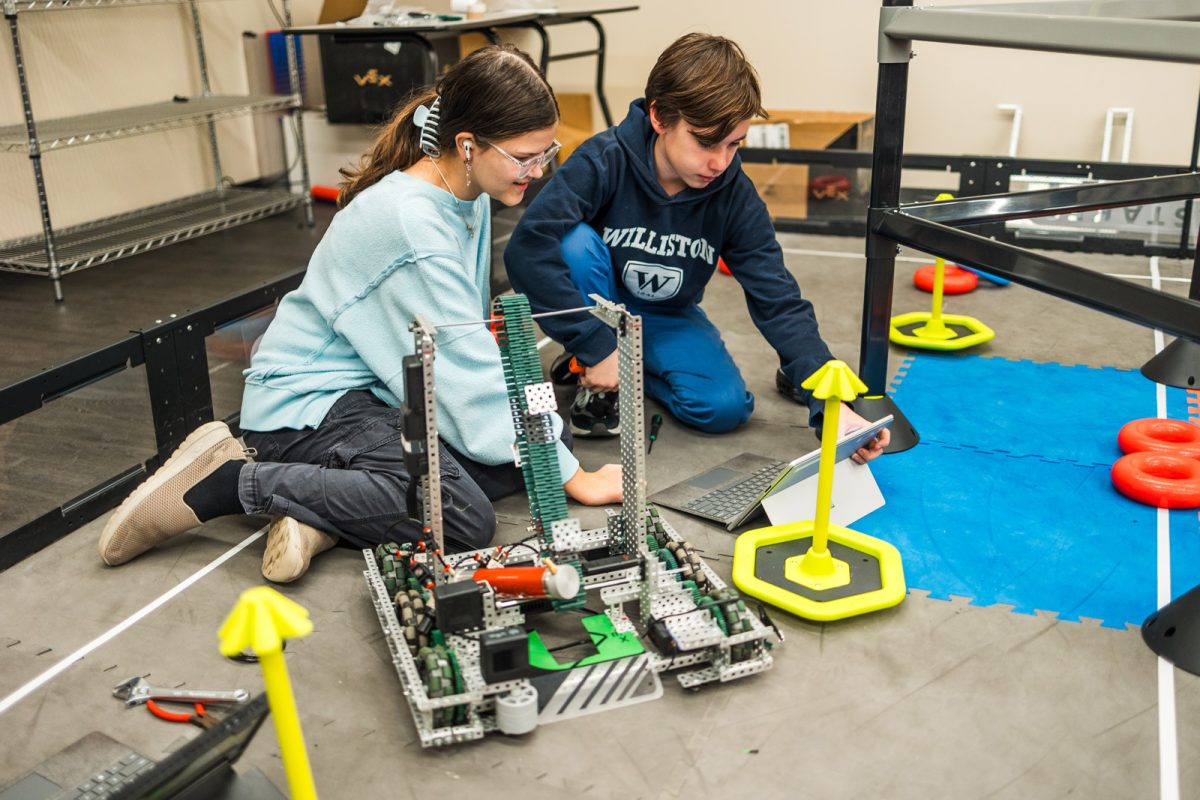

However, an example of a girl–boy pairing that are friends in and out of the classroom is sophomore international students Tracie Ngo, from Vietnam, and Ozora Yazaki, from Japan.

Tracie remarks that their friendship is more based on other aspects of their identity.

“I mean we are both Asian, we are in the same class, we have the same interest, which is more important than gender,” she said.

Ozora notes that they match each other, and he also comes from a similar background as Nasheen, being raised mostly by women.

“Our vibes are similar,” he said. “My mom, my cousins, my family are all girls except for my dad, so I’m comfortable with girls.” Ozora added that he thinks less frequent mixed-gender pairing could also be due to cultural differences. He notices it is less common in the United States.

These divides, no matter how or why they form, are impacting our educational and social experience.

Wakanda finds that it hurts us when we cannot talk to everyone.

“I do think it affects our educational experience because if I can talk to 100% of people in the room that would be so much better than being able to talk to 50% of the people,” she said.

The anonymous senior girl sees it as us losing an opportunity to learn.

“I think it closes us off to opportunity because it is different being friends with a guy than it is being friends with a girl,” she said. “I’ve learned a lot more and I understand a lot more because I’m friends with a bunch of people.”

Nasheen believes such divides negate the idea of diversity, and Ava thinks we should lean into the discomfort in class, at least at moments.

“I think that when people make groups among each other instead of the teacher making the groups, we tend to go towards that comfort,” she said. “It makes you feel safe, but it is also healthy to not always feel that comfort, because when you put yourself out there, that is when you make new friends and listen to other people’s experiences.”

So how do we remedy it, if at all?

Mr. Brooks thinks you cannot force it but instead point it out so people can be aware.

“I don’t actively try to combat it because my feeling is that my priority as a teacher is to have students feel that it’s their space to be free to express themselves however they wish,” he said. “But I do like to hold up a mirror.” He adds, “If you don’t know it’s happening you can’t make a conscious choice.”

He does, however, assign groups, but more so to connect the class in general.

“I randomize groups, so people end up having to work together. I don’t do it specifically to heal a gender divide. I do it so people can meet other people. I think the idea of having to bring genders together implies a binary. In reality it is about people getting together to humanize one another.”

Sarah Levine, an English teacher for both seniors and middle schoolers, creates classroom unity by uniting them under a common goal.

“For my middle schoolers I used to do a thing called ‘points,’ where we would earn a certain amount of points from good class behavior, everyone turning their homework in on time, and everyone supporting each other,” she said. “After earning a certain amount of points then we would all go to the gym and play games together or go get ice cream at Mt. Tom’s or some sort of activity where we feel like a class, where we feel like a unit … Once we get those points there is a general respect for each other and energy and kindness. People tend to be more relaxed, inclusive, and excited.”

Levine finds making a classroom environment that is comfortable for everyone takes time.

“It takes time for me, to just establish trust, for people to get to know each other either through group work, discussions, partner work, writing, reading, and grappling different text which is an amazing way of expressing vulnerability and getting people comfortable,” she said. “But generally, just time, it’s not something I want to rush.”

Sebastian • Sep 19, 2024 at 5:29 PM

This is the best article the Willistonian has ever seen, possibly even the world.