Sophomores Raise Awareness for Indigenous Children’s Rights

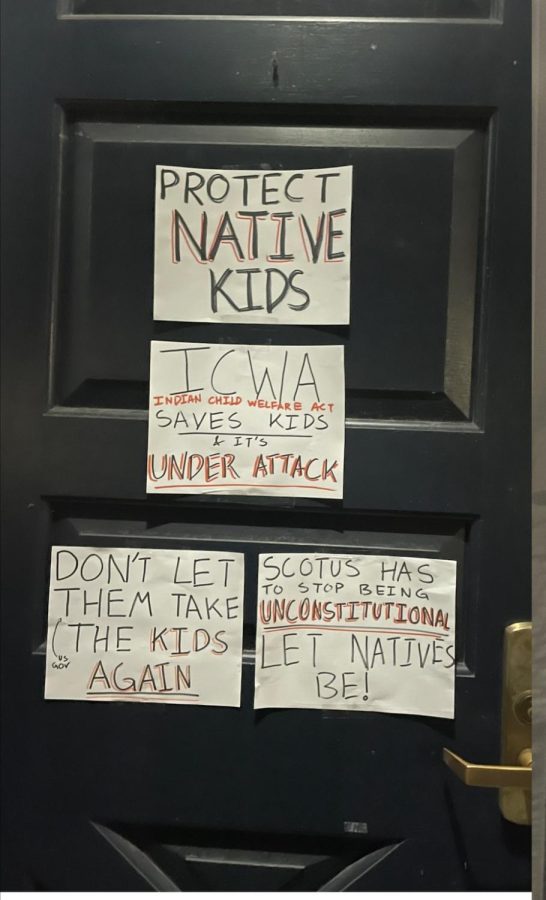

Hand-made signs calling attention to Indigenous people and their land recently appeared on many locations around campus, and are tied to a potentially landmark upcoming Supreme Court case.

Early morning on Oct. 17, as students and faculty were walking to class, signs reading: “THIS IS INDIGENOUS LAND” and “PROTECT NATIVE KIDS” were spotted all around campus, including on the doors to Reed, the Schoolhouse, and Scott Hall.

Indigenous People’s Day, formerly known as Columbus Day, is a day for Americans to respect and learn about the cultures of native people as well as a symbolic protest against European colonizers who began centuries of oppression when, upon arrival in North America in the late 1400s, nearly wiped out an entire population. First declared a national holiday in 1934 and a federal holiday in 1971, Indigenous People’s Day shifts the focus from Columbus, a man of discovery but also massacre, to respecting those who inhabited North America before the Europeans.

Two sophomores, Parker Brown and Chris Anderson, were the ones who decided to put their activism to use and put the signs up.

Parker provided a descriptive explanation of the recent political controversy of the ICWA, which served as the impetus for the poster hanging.

“ICWA is the Indian Child Welfare Act that was instated in 1970 and stated Indigenous children that are no longer under legal guardianship of blood relatives must be placed in an Indigenous household,” Parker said. “This is due to Indigenous activists stating how traumatizing it is to be placed in a white household and be stripped of many parts of their culture.”

Parker commented on the history of Indigenous oppression, and wanted the signs she and Chris put up around campus to make others aware.

“Often times prior to ICWA, being placed in a system with white families was a huge part of why residential schools were legal,” Parker said. “The Supreme Court is reviewing this act on November 9, and when it popped up on my news feed I just couldn’t go to sleep without trying to do something, even if it was just in our small community.”

On Nov. 9, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in Haaland v. Brackeen, which will examine the constitutionality of the ICWA.

These residential schools in Canada thrived from the 1880s to the early 20th century by forcibly separating Indigenous children from their tribes and families, and putting them into boarding schools which deprived them of any Indigenous culture and language. The attempts to “Westernize” the Indigenous children included cutting their hair, no longer being called their tribal names, and severe physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

A statistic in 1907 from a governmental medical inspector stated that 24% of healthy Indigenous children were dying in residential schools at this time period. Furthermore, anywhere from 47-75% of students “discharged” from these schools to home quickly died. According to IWGIA (International Group Work for Indigenous Affairs), only 2% of the U.S. population identifies as either Native American or Alaskan Native today.

Lucy Hoyt, a sophomore from Hatfield, Mass., was unaware that the ICWA Supreme Court decision was even happening.

“I didn’t even know there was a possibility of it getting overturned,” Lucy said. “It’s not getting a lot of publicity.”

Many may assume that indigenous conflicts are old history, but many cases have recently arisen in addition to the potential removal of ICWA. In 2019, British Columbia ended the long practice of “birth alerts,” a system that highlighted potential high-risk mothers involved in child welfare cases (without their permission). Not only was this practice non-consensual, but it was overwhelmingly aimed at Indigenous mothers.